Winners and losers from Oxford Economics’ report on manufacturing job growth across US metros

US manufacturing ebbs and flows across multiple industries. For communities intent on matching economic assets with emerging opportunities, the future is bright.

Sometime in April, if it hasn’t happened already, US manufacturing employment will surge past 13 million total jobs for the first time since November 2008. Back then, manufacturing was in a free fall from its all-time high in May 1979, when the sector employed almost 20 million Americans — the most ever.

But US manufacturing’s modern iteration is different, its industries varied from 1979.

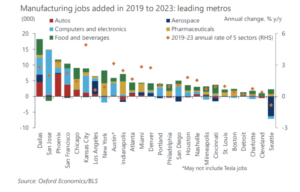

Oxford Economics is helping us sort out manufacturing’s new personality with its recent analysis of manufacturing job growth across industries – in this case the five sectors (I’ll use ‘sector’ interchangeably with ‘industry’) leading manufacturing’s employment comeback.

The sectors are automotive, computer and electronics, food and beverage, aerospace, and pharmaceuticals. The cities benefitting most are:

- Dallas

- San Jose

- Phoenix

- San Francisco

- Chicago

Here’s the data, charted (click here for a bigger graph):

Aside from the obvious top five, here’s my take on winners and losers from the report:

Winners

America’s food and beverage ecosystem is a juggernaut. US F&B manufacturers added 400,000 jobs in the 2010’s and today, most every US metro is home to an innovative, increasingly automated F&B sector.

The community is an innovation machine. It’s also local, it’s well-funded, it’s authentic most of the time (Expo West was a greenwashing festival), it supports rural redevelopment and farmers — and it’s increasingly automated. It all adds up to growth.

Everyone hates on California. To listen to its critics, California’s business community, led by an exodus of manufacturers, is being hollowed out by EVs and bullet trains and taxes and DEI.

But if manufacturing is defined by its diversity, the cross-industry panoply developing here leaves it well positioned. From aerospace in Los Angeles, to “technofacturing” in the Bay Area, to a state-wide automotive supply chain second to none, if California can get out of its own way, manufacturing may bring the besieged state all the way back.

It will be fascinating to review this same chart in five years. What’s happening in south-central Texas may reshape US manufacturing for a generation.

Tesla’s enormous Austin factory is one giant magnet for new business – but just a few miles to the northwest, Samsung is anchoring a semiconductor ecosystem to rival any emerging industrial community in the US – including its TSCM/Intel counterpart rising in the Arizona desert.

Dallas is a city playing to its strengths. Diversity is a social and economic calling card here – and manufacturing is both a beneficiary and an engine of growth. Dallas doesn’t get the manufacturing headlines of its Texas neighbors, but numbers don’t lie in this case. As in #1.

Much like Texas cities, Phoenix is opportunistic, building a business-friendly reputation on available real estate, a population influx, and deliberate strategy to embrace manufacturing. It’s not so much that one attribute or another is a draw; it’s that combined, the sum of the parts happens to align with the needs of manufacturing companies in specific industries.

The key is being deliberate around packaging-up community assets to pursue new manufacturing opportunities in lieu of others.

Losers

On one hand, it’s hard to label an industrial epicenter like Chicago, as a loser relating in anything manufacturing-related – and it’s in the top five on this list.

But are its modern attributes lost in its size and reputation? A giant in agribusiness, chemical and pharmaceuticals, fabrication, and way more, it’s small business community of manufacturers, across multiple industries, is arguably the most compelling ecosystem in the US.

Chicago must aspire to be #1 on this list, the national leader in employment growth. Full stop.

Denver has no such aspiration, and it shows. Its food and beverage sector including a capable and diverse co-manufacturing ecosystem is a national draw for CPG companies, money, and talent (see above), but community leaders here are enamored with the tech industry.

That’s not a bad thing. The plan to chase tech will pay off. Meanwhile, as Denver leans in to a lifestyle-and-high-tech-or-bust approach, Huntsville, AL, its Space Command rival, leans into creating aerospace manufacturing jobs, and today Denver lags behind its more ambitious, smaller counterpart. It says a lot about Denver’s priorities.

Even if Seattle’s diminished aerospace sector can be chalked up to the struggles of its embattled icon (more on that next time), it’s still disappointing that the town’s fabled innovation ethos isn’t translating to more robust growth, to a maker-community jobs engine. Yes, much is percolating in food and beverage as locavore trends are as pronounced here as elsewhere. But this compelling city, as with others here in the L column, will hopefully show better in the next five years than they do now.

Manufacturing beckons. Who’s in?

Bart Taylor is a BDE at Moss Adams and founder and former publisher of CompanyWeek media. Reach him at bart.taylor@mossadams.com.